On the Horse

He stumbled away for good then. Part of me was heartbroken for this sad old Japanese man who drank too much. A bigger part of me, however, felt only smugness for his acceptance of me while the two judgmental sisters stewed.

*

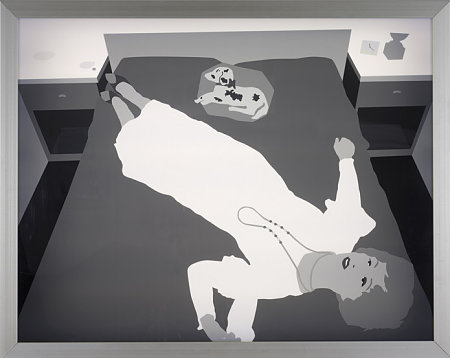

It’s now 2015. My wife Katie and I are tenured university professors. We live on a small lake in rural Illinois, once the stomping grounds of the Miami tribe. We get up early with the dogs and sit on the couch with our coffee and our books. Occasionally, we look out the window and watch the sun rise from the earth beyond the lake, its rays pouring through the trees and bringing to light the Canadian geese lazily gliding across the water. I turned fifty this year, an age that leaves me wondering, How did I get here, with this beautiful wife and this beautiful house?

Seventy years ago, while their Japanese contemporaries burned, my father, aged seven, and my mother, aged six, soaked in the summer sun, months away from the cold blast of a Buffalo winter. During the war, my mother had nightmares about being in a bombing raid, but just nightmares they remained. My father and his friends pretended they were “pissing on Hitler” at the school urinals. When they played at soldier, that’s what it was: play. Soon after VJ Day, my parents went back to school for the first time without the specter of war hanging above them. The rubber and metal drives ended, and soon so went the rationing. The men came home. Some took advantage of the GI bill; others worked in the factories that churned out the finished goods desperately needed in Europe. America entered the period of its greatest growth. My parents, safely ensconced in white suburbia, met in high school. Unlike their parents, they attended college. Soon after, they married and raised five children, all of whom are still alive today.

Shigeru Orimen and Nobuko Oshita did not meet in high school, did not go to college, did not marry, and did not have children. Instead they left behind a lunch box and a home-made slip.

In Ursula LeGuin’s astonishing short story (what makes it a short story is difficult to say, since it has no plot or protagonist) “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” a small child of indeterminate gender and age lives in a closet, sitting in its own excrement. The child is not allowed to leave, and no one is ever permitted to speak a kind word to it. The city of Omelas is a wondrous place, a utopia grander than El Dorado. Citizens sometimes visit the child, and “all know that it has to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.” The child lives on corn meal and grease. Some visitors want to clean the child, feed it, take it by the hand and raise it as their own, but they don’t, for “if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed.”

Anyone who reads the story becomes the protagonist faced with the same decision: Do I stay in paradise or walk away from it?

I stay. Every day. I know the good life I live has been made possible through the deaths of others, and I know people, including children, continue to die for my benefit, even for stupid things like cheap gas. Still I remain in my own little Omelas.