Aisle

They wouldn’t buy apples from the orchards

because of the chemicals that would kill them,

maybe not right away, but in time. The blooms

caught the air off the river as intended

so that the child wanted to walk between them

down the hallways they formed, a path in a temple

or cathedral, but no, she mustn’t ever.

And so it had been all along the uplands above the river:

migrant workers moved through unseen a few weeks each year,

following the harvests, so many orchards

farther south that owners built cinderblock quarters.

Her mother pulled apples from pyramids

at the store, solid red or yellow, skin so hard

she peeled them, like eating wet sand without flavor.

Local fruit had been taken by train, then truck

to the city until it wasn’t anymore, left

to be sold roadside by the peck or bushel.

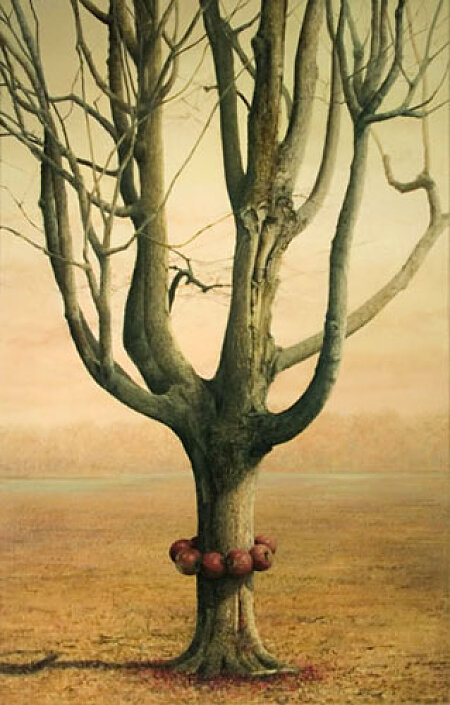

You can tell orchards are apples by the silver,

not from bark or flowers but the leaves,

like a storm coming, like the story of an old woman

who was royalty become ugly

so she could administer poison. The apple fell

from the girl’s hand and she slept like a statue,

like the dead, her body never decaying and she unable

to wake unless she be loved and no one loved her

because they knew of her hunger.

This was a real place: miles of apples and no angels,

no flames but sometimes in the spring.

To try to fight a freeze when fruit was setting,

they built fires and made the smoke start crawling.