On the Marking of Years

14.

Once, when Sophie was six, and Paul one, we lost all our passports on the airplane to Montreal. My only memory of the city is a windowless room in the consulate. We had to go both to the French one and the U.S. one due to my husband’s having only a French passport.

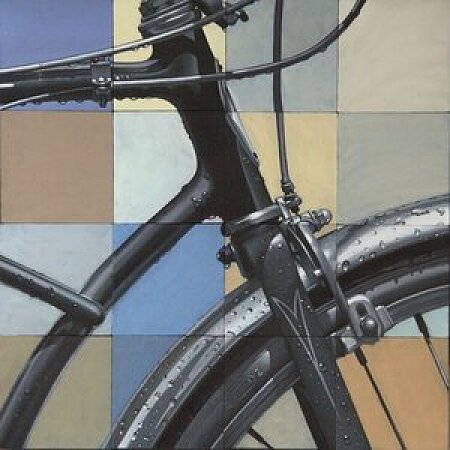

The windowless room had square tiles and a camera on the ceiling with a big dark eye. It blinked red at times and seemed to move. No electronics were allowed. No laptops. No beeping toys. Sophie was very excited at first and skipped all across the tiles. Then she asked me how long we’d have to wait. I said I didn’t know. She whined, then cried, then stared up at that camera eye, asking for someone to come get us, for someone to hear.

I had no experience with truly terrible desperation, but that small desperation was enough. It was all I could do to wait for that hour or two and tell her we would be fine. I lied, pushing off my own doubt, and told her that the people in the other room knew we were there. They would come find us when they were ready.

After two hours, I took her hand and found an unlocked door at the back. I told her to run. We ran without stopping up the stairs. A bored-looking man with a guard dog, smoking a cigarette, told me he’d forgotten about us.

“Good thing you reminded me you were alive,” he said.

I would remember that man for years, though not the details of his face. Only the shadow that fell over the room when he told us, still, my husband’s interview was not finished. We would not, as of yet at least, be allowed to leave. I told myself I would have to bring my daughter joy some other way. I would let her skip and skip for hours. I would do anything to push that shadow away. I would not let her see the doubt that had crept into my bones.

15.

Sophie is fond of saying, “That ship has sailed,” when what she really means is, “I am very tired.” I am fond of saying, “When I wake up, it is with my hands in my pockets, and a sort of existential dread.” I do not say this out loud, of course. I say it only as a secret, hoping perhaps someone will overhear. And I am relieved when, as always happens, no one does.

At Sophie’s school, they have to wear masks nearly all day, with a few breaks. I almost wrote mass. And I have bought her cloth ones from online, some with purple cloud-like patterns, others with star shapes, others that are unnaturally shiny but dark. She wears them every day and complains that her skin is starting to protest. She shows me the small eruptions on her cheeks. I tell her that one day she will not have to wear them, and her skin will go back to normal again.

And when’s that? she asks me, and I tell her it’ll be gradual. You’ll probably have to keep wearing them on planes for a while.

“Well, I’m not going on planes for at least two years,” she says.