My Murder Suicide

At the end of my college days, things with her were messy. Our band broke up during a humiliating onstage fight, after which I lobbied to kick her out of the house we shared with friends. I can’t deal with her drama anymore, I said in my world-weary, twenty-one-year-old way. My friends struck a deal. No drama would enter my sphere. They would be her shoulder to cry on, the sounding board for her outbursts. Mostly I steered clear. I tucked myself away in my bedroom, let the rest of the household have their fun while I numbed myself on pot and Solitaire. I was already dreaming of life after college, away from the tight emotional quarters and noise and mess of college life. I don’t remember saying good-bye, but I’m sure I was polite. Our farewell hug was stiff. Things between us during those last few college months were as polite as polished silver.

A few years after graduation, we reconciled at a party during one of my visits to the east coast. There were no more bands, no more boys, no more living in too-close quarters so that we gathered static like socks on shag and sparked a thousand tiny shocks. What had we fought about, anyway?

Fifteen years after our reconciliation, our band reunited. Before the show, we met at the drummer’s house to practice. Bedraggled from a cross-country red-eye, I sat on the front step of our drummer’s house and watched cars drive too fast down the suburban street. A car stopped, reversed, parked at the curb. I felt a stutter in my chest. The lead singer stepped out of the car. Her face lit up when she saw me, a smile spread across her lips. We said each other’s names like they had been waiting in our mouths all along, like we had missed forming the syllables all those years. She always did say my name like it was a private joke between us, like I was a singular planet in her solar system.

I think of all the times she could have died. The suicides she threatened but never attempted. The alcohol poisonings. The night we stood atop a crumbling stone wall by the town cemetery, high on mushrooms. The dark places she seemed to have banished to the past now that she, that we, had reached middle age. During a break from our band practice, we sat on the back porch of our drummer’s house. She made fun of herself for taking the psychiatric drugs that she had railed against when we were college students. She wrote a song about the doctors who kept suggesting that brain chemistry could be to blame for her problems: There’s something wrong inside your head / At least that’s what the doctor said. Back then, she refused medication, took pride in not falling prey to the pharmaceutical industry’s Prozac solutions. She laughed about being a hypocrite now that she was taking the medicine she had once shunned.

“They keep me even,” she said with a shrug.

“Whatever works,” I said.

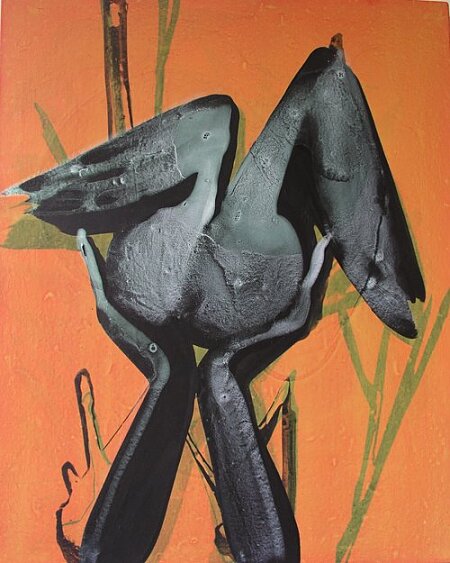

Over the course of the reunion, we realized that our lives had entwined before we grew in different directions. The past arguments and anger had seeped into the soil of our friendship and had nourished what we were now. Even though we reached for our own separate suns, we remained tangled at our roots. We could finally appreciate who we had been, what we meant to each other, and the people we had become.